Automated Acceptance Criteria

I have a dream (Story Card)

What is my dream story card? I don't mean: What's the story I'd most like to work on! I mean: What should a virtual story card look like (as opposed to card stock on a wall)? This may be a trivial question. But for me the user experience working with stories is very important: I work with them daily, write them, discuss them, work on them, accept them, etc. I want the feel of the card to be thoughtful, like that fellow to the right.

And more than that. I am lazy, impatient, hubristic. The acceptance criteria, I want them testable, literally testable in that each has a matching test I can execute. Given my laziness, I don't want to switch systems and run tests; I'd like to execute acceptance criteria directly from the story card.

So is there a system like that today? No. There are bits and pieces though.

Not all story card systems are equal

Some story card systems are particularly awkward to read, understand or use. Special demerits for:

- A hard-coded workflow that the team cannot be change to fit how they work: the team is expected to fit the tool

- Workflow state transition buttons are nice, but not so nice is unconfigurable labels, especially when the button labels are misleading

- A hard-coded or limited hierarchy of stories, so if a team uses epics or features or themes or whatever to organize stories, and there are more than one level to this, the team is out of luck

- Lack of quality RESTful support, in particular, no simple identifier for story cards, so linking directly to cards is opaque, useless or completely absent

A scenario

Post-development testing on this team is a fairly ordinary role. The developers say: a new web page is ready. Testers then validate the same page features each time for each new page, simple things:

- Can an account with security role X log in?

- Can X submit the form? (Or not submit if forbidden?)

- What form defaults appear for role X? Do they reflect role X?

(Yes, I know — what about developer testing? Bear with me.)

On it goes, the same work each time. Redundant, repetitive, error-prone, fiddly. And worst of all—boring, BORING! This is traditional, manual "user testing" at its worst.

What's to be done? Can we fix this?

After all, the testing is valuable: nobody wants broken web pages; everybody wants to log in. But the tester is valuable, too, more valuable even: is this the most valuable testing a human could do? Surely people are more clever, more insightful than this. And what about all the other page features not tested because of time spent on the basics?

Well, people are more clever than this.

Clearing the path

What guides testing? If you're using nearly any form of modern user story writing, this includes something like "Acceptance Criteria". These are the gates that permit story development to be called successful: the testers are gatekeepers in the manual testing world. In the manual world these criteria might be congregated into a single "Requirements Document" or similar (think: big, upfront design).

We can do better! Gatekeeper-style testing assumes a linear path from requirements to implementation to testing, just as waterfall considers these activities as distinct phases. But we know agile approaches do better than waterfall in most cases. Why should we build our teams to mirror waterfall? Of course the answer is to structure teams to look agile, just as the team itself practices agile values.

So how do we make Acceptance Criteria more agile?

Enter the Three Amigos

In current agile practice, a story card is not a ready to play until approved by the The Three Amigos: BA, Dev, QA. Each plays their part, brings their perspective, contributes to meeting team-agreed "Definition of Ready".

A key component of playable cards are the Acceptance Criteria — answering the question, "What does success look like?" when a story is finished.

The perspectives include:

- BA: Is the story told right? — What is the way to describe the work?

- Dev: Is the story the right size? — What is the complexity of the work?

- QA: Is it the right story to tell? — What is the value of the work?

What are Acceptance Criteria?

But where does this simple testing come from? Any software delivery process beyond "winging it" has some requirements

Well-written agile stories have Acceptance Criteria. What are these? An Acceptance Criteria (AC) is a statement in a story that a tester (QA) can use to validate that all or a portion of the story is complete. The formulaic phrasing for ACs I like best is:

GIVEN some state of the world

WHEN some change happens

THEN some observable outcome results

Generally for web applications this means when I do something with a web page in the application, then the page changes in some particular way or submits a request and the response page has some particular quality or property (or the negative case that is does not have that quality or property).

In some cases it is even simpler: just check that a particular web address fully loads, for example, when testing login access to pages.

So what's the question?

Wherever possible we want to automate. If something can be done for us by a computing machine, we don't want to spend human time on it. Humans can move on to more interesting, valuable work when existing tasks can be automated.

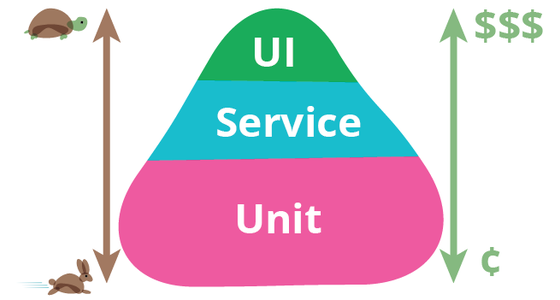

Consider the Test Pyramid (image right): automating lower-value tests focuses people on higher-value ones. You get more human attention and insight on the kinds of tests which best improve the value of software. You win more.

The Story

This is a sample story card with a simplistic implementation of AACs. Live buttons call back into the story system, to be mapped to calls in the testing system. (Another implementation might have the buttons directly call to the testing system, avoiding an extra call into the story system but showing details in the page source about the testing system.)

Title

Narrative

AS A AAC author

I WANT a mock executable story

SO THAT others can see the valueDetails

No actual criteria were validated in the execution of these tests. This is only a mock.

Acceptance criteria

Summary: 1 missing, 1 untested, 1 running, 1 passed, 1 failed, 1 errored, 1 disabledGIVEN magical thinking

WHEN in Missingland

THEN there's no testGIVEN magical thinking

WHEN in Newland

THEN nothing has happened yetGIVEN magical thinking

WHEN in Fastland

THEN tests run quicklyGIVEN magical thinking

WHEN in Happyland

THEN UnicornsGIVEN magical thinking

WHEN in Sadland

THEN there be DragonsGIVEN magical thinking

WHEN in Crazyland

THEN nothing works rightGIVEN magical thinking

WHEN in Slowland

THEN tests are disabled

Acceptance Criteria states

Every AC potentially has a message from the testing system giving more detail on state. These are noted below.

- Missing

-

This AC has no matching test in the testing system. Use the Create button to create a new test. This does not run the test.

The message is boilerplate to remind users to create tests.

- Untested

-

The AC has a matching test in the testing system, but the test has never been run. Use the Test button to run the test.

Typically there is no message for this state.

- Running

-

The matching test for the AC is running in the testing system. Use the Cancel button to stop the test, or wait for it to complete.

The message, is supported by the testing system, should give a notion of progress. See REST and long-running jobs for how to do this.

- Passed

-

The matching test for the AC passed last time it ran. Use the Test button to run the test again.

Typically there is no message for this state.

- Failed

-

The matching test for the AC failed last time it ran. Use the Test button to run the test again.

The message must give a notion of why the test failed.

- Errored

-

The matching test for the AC errored last time it ran. Use the Test button to run the test again.

The message must give a notion of why the test errored.

- Disabled

-

The matching test for the AC is disabled in the testing system. Update the testing system to reenable.

The message, if supported, should give a reason the test is disabled when available.

Potential problems

Nothing is free. Potential problems with AACs include:

- Integrations

-

There are no existing integrations along these lines. You need to build your own against JIRA, Mingle, FitNesse, Cucumber, etc. Whether the story system drives the interaction, or the test system does, may depend on the exact combination. Best would be if both systems can call the other.

- Scaling

-

As more AACs run, the complete suite takes longer. For example, adding 1 minute of AAC/story, and 5 stories/iteration, in a 12 iteration project takes 60 minutes to run. This is not specific to AACs but a general problem with acceptance tests. It's still much cheaper than the manual steps for each test, but prohibitive for a developer to run the whole suite locally.

Best practice is for the 3 amigos to run only the tests specific to a story before calling that story Ready to Accept.

Update

Until I published this post on Blogger, I really wasn't certain how it would look on that platform. I manually tested the visuals from Chrome with the local post, and it looked good. After seeing it in Blogger, however, the "aside" sections are laid out poorly, overlapping the text. I won't relay the page: mistakes are the best way to improve, and a subtext of this post is Experiment & Learn Rapidly. Public experiements are the most faithful kind: no opportunity to fudge and pretend all was well on the first try.